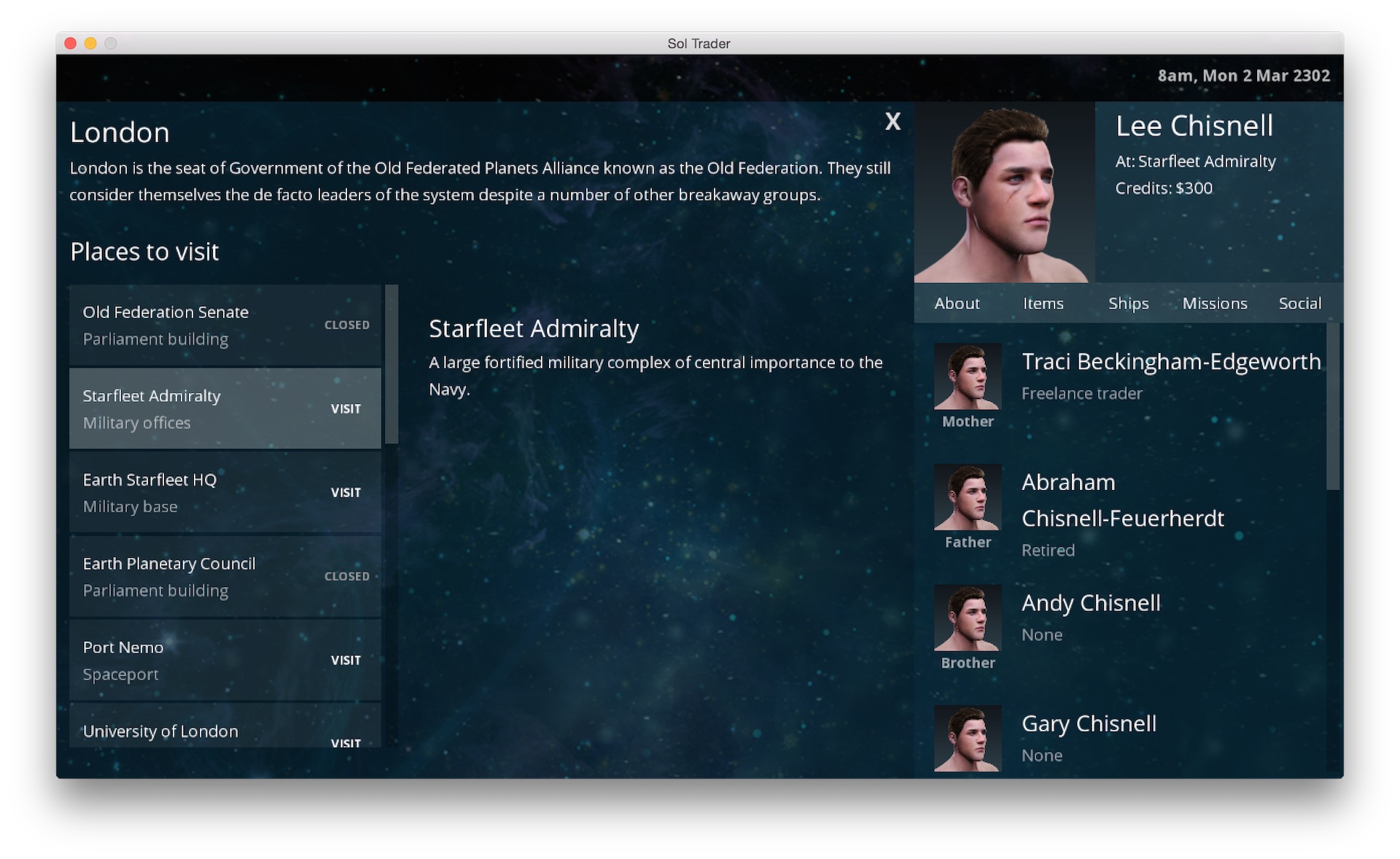

I’ve been working on the city interaction screens this week on Sol Trader, shown above. I’ve been considering how to implement the ‘business as usual’ tasks that players complete on landing at a city, such as filling the fuel tank, repairing their ship, or buying and selling trade commodities.

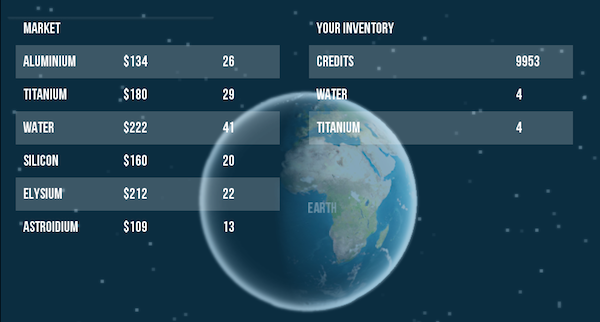

Here’s the city market screen from the old prototype version of the game:

I could bring this up to date and polish it for the current look of the game, but considering this has brought up an important gameplay question.

Do I make the interaction between the player and the organisations purely a GUI experience, or do I make the player interact with the employees of the organisation to achieve their goals?

For example, instead of clicking on a table view like the one above, players would head to the market, start a conversation with a broker, state what they wanted and get a price direct from them. Which is better?

For a number of reasons, I’ve chosen the less realistic ‘interaction with employees’ option for now. Here’s why.

Focusing on a compelling vision of fun

It’s easier for the player to buy goods from a tabular view like the one above, by just clicking on what they want. It’s efficient and fast. It also isn’t very realistic to make these interactions personal, especially for the 24th century. Much of our interaction with organisations is via an automated system these days, and I would hazard a guess that this is only going to increase as the years pass.

However, my game is all about relationships: the friendships that the player forges during both the pre-game history generation and whilst playing the game. When at cities, players are getting ships fixed, finding contract work and buying and selling goods. If I make this daily business solely done through interacting with in-game individuals, then the game won’t feel nearly as impersonal and cold. The game isn’t about making stacks of money or buying the biggest ship as fast as possible (although players could do that if they wanted) - it’s about the interactions with the individuals along the way.

I want to create a game where players will genuinely look forward to landing at a certain remote city to catch up with an old friend whilst upgrading their ships, or actively avoiding a certain hotel through a poor relationship with the manager. That sounds fun to me, and that’s what’s going to keep people coming back to the game. Having a compelling vision of what the fun looks like is essential to ensuring we stay on target with our design.

It might not be ‘realistic’ but fun is more important than realism every time. The only important type of realism in a game is a ‘sense of realism’. Players should be able to suspend disbelief long enough to immerse themselves in the world we’ve created.

The right decision isn’t always the easiest to implement

This decision causes some design headaches. If the only way to do business with an organisation is through an AI employee, this means a few things:

- The conversation engine has to be top notch. I’m just about to start working on this and I’m doing my research first to find out the best way to make this work well.

- What happens if a job is vacant? If no-one took a certain job though history generation, then potentially that organisation cannot be interacted with at all. The way I’m handling this is to have the concept of ‘essential jobs’. Certain jobs simply have to have someone doing them. Just after history generation we trawl through all the eligible characters in the game and match them to these jobs.

We’ve added more complexity to the code base, but some extra work is justified. It’s very easy to simply choose the option that’s easier (or cleaner) to code, but that’s how we end up with poor design and no fun.

Finding the fun is hard work

Once we have a decision, it’s important to implement our chosen solution as quickly as possible and then to play around with it, to see if it captures the fun that we’re looking for.

Fun in games is something that has to be worked for. It doesn’t appear without effort. Our raw materials are art assets, sound files and code: we grind them together searching for the fun in the midst of the three. The formula is elusive and uncertain, and it can take hours of effort, but eventually our game will catch light and burn bright, almost like magic.

It’s very important not to gold-plate game code too early. Jumping to ‘clean well-factored code’ too early is dangerous: it’s essential for maintenance, but overdoing refactoring too early is a failure to understand that we’re in the complex Cynefin space. We could well be throwing everything away. As long as we don’t neglect code cleanup once we’ve found what works, hammering in a basic solution minimises the potential of wasted effort.

Summary: beware realism

-- Tynan Sylvester, The Simulation Dream

Beware realism. It sounds like the holy grail of game development, and it’s very enticing to us developers. Ultimately however it can pull us away from what’s fun to play.

An appearance of realism is what we’re actually looking for, and this can be a very different thing.

I’ll post an update when I’ve got this interaction into the game, to see whether it does indeed give us the fun we’re looking for. Stay tuned!

Check out my indie game Sol Trader, an epic space action adventure. Be part of a living society you can befriend, understand and manipulate to your own ends.

Follow